Homily for the Fourth Sunday of Lent Year A 2020

Readings: 1Sam 16:1-13; Eph 5:8-14; John 9:1-41

22 March 2020

This is my first online homily to a virtual congregation in the era of the virus here at Newman College.

In Geraldine Brooks’ novel Year of Wonders, the plague comes to the small village of Eyam in Derbyshire in 1666 and the residents decide to quarantine themselves. The rector of the church is a visionary and a leader of the community. But in the end, he breaks. When someone comes to the manse seeking one more pastoral favour for her beleaguered family, he tells the supplicant: ‘If your mother seeks me out to give her absolution like a Papist, then she has made a long and uncomfortable journey to no end. Let her speak direct to God to ask forgiveness for her conduct. But I fear she may find Him a poor listener, as many of us here have done.’

After a century without anything like a pandemic coming to our shores, 80 years after the great depression, and 75 years since the last world war, most of us have never known anything like the uncertainty which lies just around the corner for us, our loved ones and our communities. For those who are Australian students here, not even your parents or even grandparents have experienced anything like this. For a few generations, we have thought that we would be spared catastrophes like these.

LISTEN: https://soundcloud.com/frank-brennan-6/newman-homily

We have enjoyed years of economic growth. We have harvested the good results of globalisation. Those fortunate to make it to a university like ours have realistically relished the prospect that employment, economic security and social approval would be achievable. Each generation has thought they would do it better and easier than the one before, and that was the fervent hope and desire of the previous generation. And so we have been able to dedicate some of our energies generously and voluntarily to assisting those who have not enjoyed the same benefits as have we.

Religious faith has not seemed as pressing or necessary as in past times. Spirituality has been an individual quest without need for community engagement. And adherence or commitment to any institutional church or religion has been less desirable, not only because of the general decline of trust in all institutions but also because of particular shortfalls such as the failure of the Catholic Church to address child sexual abuse by those in positions of trust and power.

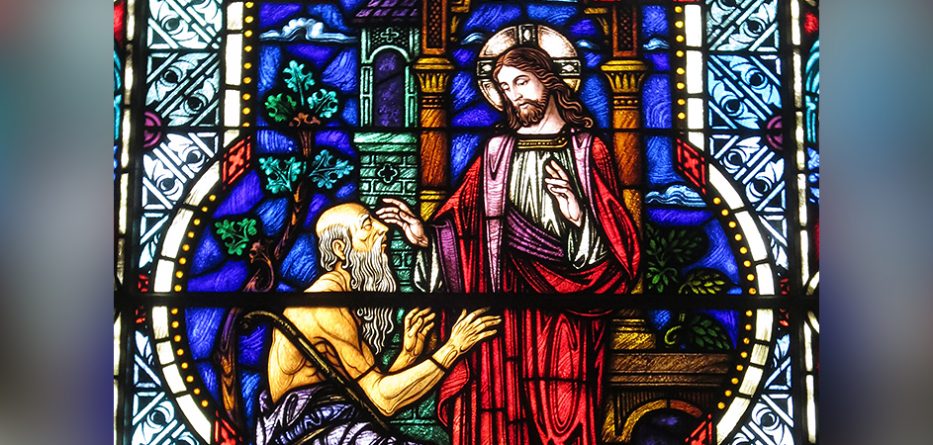

In today’s gospel for the Fourth Sunday of Lent, we witness the encounter between Jesus and the man born blind, between that man and the religious authorities, and between Jesus and those religious authorities. In the previous chapter of John’s gospel Jesus has declared:

I am the light of the world;

Anyone who follows me

Will not be walking in the dark,

But will have the light of life.

None of this goes down well with the religious authorities. With Jesus claiming, ‘Before Abraham ever was, I am’, the religious authorities pick up stones to throw at him while he is still in the temple.

Jesus leaves the temple and encounters this blind man. He’s been blind from birth. The disciples wonder who sinned – the man or his parents. In much the same way, when the coronavirus takes hold, there will be people on their hospital beds gasping and wondering what they did to deserve this. Why me? Or those unable to visit, will be asking, ‘Why my loved ones?’

As we wait – many of us obeying the dictates of physical distancing while others mass together on Bondi Beach in the sun and surf as if nothing has changed – we hear these words of Jesus:

‘As long as day lasts we must carry out the work of the one who sent me; the night will soon be here when no one can work. As long as I am in the world, I am the light of the world.’

We pray for all those at the frontlines like the doctors and health workers who will be stretched to breaking point in the weeks and months ahead.

The man born blind is cured by Jesus. He simply does what Jesus asks him to do. He goes and washes in the pond. While the blind man comes to see physically, the religious authorities become more blind spiritually. Jesus has broken the law. He has cured on the Sabbath. No matter what he does miraculously, he could never come from God. In the end, it’s the uneducated man who had been born blind who is teaching the religious authorities. He tells them, ‘God does listen to those who are devout and do his will.’ Just as the religious authorities had driven Jesus away from the temple, so too they drive away the cured man. When both those who have been driven away meet up, Jesus declares, ‘It is for judgment that I have come into the world, so that those without sight may see and those with sight turn blind.’

In this gospel story, it is the religious authorities who are so sure of themselves who are blind. It is the dependent blind man who comes to see. In Geraldine Brooks’ novel Year of Wonders, the narrator who was the maidservant to the rector’s wife notes that after a year, on the last Sunday in July, there were no new reported cases of plague in the village. The rector ‘must have marked this, too, but he did not speak of it directly. Rather, he preached a sermon on the Resurrection. The rain had been siling down for much of the preceding week, and the bare, blackened circle where our goods had been consigned to the flames was hazed all over with a hopeful wash of new green. The rector drew all our eyes there. “See my friends? Life endures. And as fire cannot quench the living spark in a humble patch of grass, neither can our souls be quenched by death, nor our spirits by suffering.”’

The rector and his wife then debated in the following week whether it was time to lift the quarantine and hold a service of Thanksgiving. The wife pointed out that many families had suffered much and wanted to be reunited with their loved ones. The wife says, ‘as you judge best, husband. But I implore you, do not make these people wait forever. Not everyone is made as firm of purpose as you.’ And so the quarantine was lifted and a service of thanksgiving was set down for two weeks later. No sooner had the rector invited the congregation, ‘Let’s give thanks’, and a crazed parishioner who had lost all her children in the plague came forward carrying her dead baby and brandishing a knife. The rector and his wife try to placate her. She and the rector’s wife end up stabbed to death at the grieving mother’s hand.

The rector’s predecessor called daily to check on his well-being. On his last visit, he told the maidservant, ‘I think grief has undone him, yes; quite undone him. I don’t think he comprehended any part of what I said to him. Why else would he laugh when I advised him to accept God’s will?’

All of us are blind to what lies ahead in these months to come. There are no simple smart answers – medical, economic or spiritual. All of us will be thrown back to the core beliefs that sustain us and make life not only bearable but meaningful, authentic and fulfilling. Whatever of physical distancing, we need to do this together. Whatever our religious yearnings or none, we need to have our blindness cured and to see that we do not walk alone, and that mortality, fragility and suffering are constitutive of humanity no matter what our gifts or talents.

For us Christians, we believe that Jesus who has gone before us has walked that path even through death and into new life. Whatever becomes of us and our loved ones in the months to come, be assured that Jesus is a good listener. Forgiveness is always at hand. We are offered new sight and fresh insight even in the midst of plague.

Fr Frank Brennan SJ is the Rector of Newman College, Melbourne and the former CEO of Catholic Social Services Australia (CSSA).