In the previous instalment of my analysis of Dei Verbum (DV)’s second chapter, I explained how the Church defines Sacred Tradition, and how we are to understand its development and growth. In this article, I will explore how Tradition grows through theological study, lived experience, and the preaching of bishops.

DV tells us:

The perception of both the deeds and the words handed down grows, from the contemplation and study of believers, who gather these things in their heart, from an intimate understanding of the spiritual matters which they experience, and from the preaching of those who have received, with succession to the episcopate, the sure charism of truth. (DV 8, emphases added)

This passage lays out the three modes by which Tradition develops in the Church. Contemplation and study refer to theology, which is the task of seeking to understand the faith (fides quaerens intellectum). I have already shown how the work of Catholic theologians prior to and even at the Council contributed to its documents and decisions. When they publish books and articles, theologians’ prime goal is to contribute to the theological community’s overall understanding. The everyday work of ordinary theologians (like yours truly) should not be undervalued by Catholics (though often it is), even as certain theologians have so stood out, like St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Alphonsus Liguori, that they have received from the Roman church the title “Doctor of the Church.” On this very topic of the development of doctrine, I strongly recommend St. John Henry Newman’s Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. Newman is sometimes called the “father of Vatican II,” because his theology played such an important role in contributing to the Council’s theology.

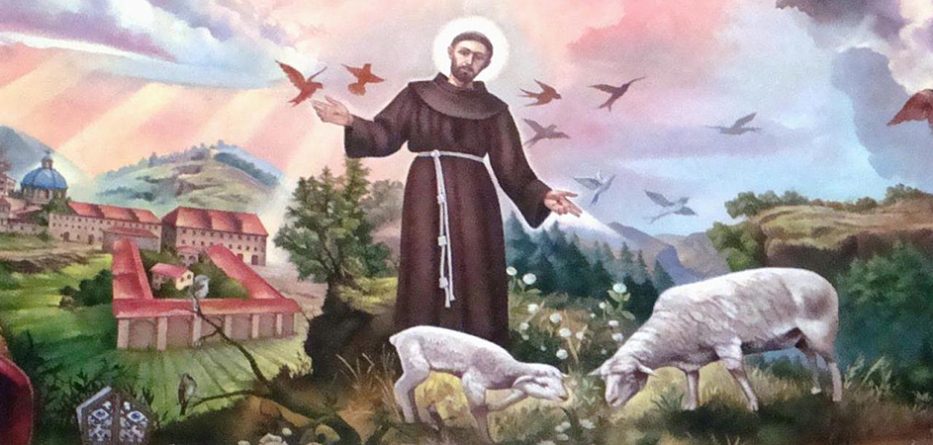

The second category may be less familiar to the average Catholic: their own spiritual experience. Since the Christian faith, as I discussed in my posts on chapter 1, is not a body of ideas but “an encounter with a person,” the experience of ordinary Christians living out their faith is itself a source for the development of Tradition. In this regard, certain key figures again stand out, such as St. Francis of Assisi or Dorothy Day. Although they were neither bishops nor theologians, they both contributed greatly to the Tradition through their writings and spiritual lives. But let us not think so narrowly: every Christian is called to contribute to the Church’s growth. Spiritual experience expresses itself in so many diverse ways that it would be impossible to list them. Everyone can think of the positive spiritual influence of people in their own families, parishes, and schools. We have also seen a dramatic example of the value of experience with the explosion of lay movements within Catholicism in the twentieth century, such as Communion and Liberation, Focolare, and the charismatic renewal. These movements—as well as the gifts, deeds, and writings of countless individuals—contribute to the Catholic Church and Tradition.

The third category, the preaching of bishops, requires little explanation. By their teaching, the bishops contribute to the growth of Tradition. It is important to point out, as DV does, that they do not only “guard” God’s word, as important as that is, but also “explain” it (DV 10). It is not the static handing over of an antique relic, which would require no special gift at all. In each age, it requires fresh explanation in accord with the “signs of the times.” Individual bishops may contribute personally to the Tradition if they are particularly gifted,[1] but primarily they do it collectively in their capacity as the Magisterium, in communion with the pope. DV points out that “The duty of authentically interpreting God’s word, written or handed down, has been entrusted to the living magisterium of the Church alone” (DV 10). Its teachings, from Nicaea to Pope Francis’s Laudato Si’, Amoris Laetitia, and Querida Amazonia, are integral to Sacred Tradition.

Over nearly 2000 years of history, the Tradition has grown considerably. No element of it can be written off because it postdates some arbitrarily-imposed, imaginary cut-off.[2] There is no “pristine” (original) version of Christianity we can go back to. Rather the reverse: the Church at the time of the apostles was only the mustard seed (Matt 13:31-32). We would not imitate it even if we knew exactly what it was. We are journeying toward the full “tree” of God’s kingdom. Who knows how far along we are? Maybe Christ will not return until the year 10,000 or 10,000,000. If this turns out to be the case, Vatican II will one day be called one of the “ancient Councils” and Francis one of the “ancient popes.”

Where will the Tradition go next? Some Catholics worry about the next synod, ecumenical council, or pope. I do not know what the Church will look 100 or even 10 years from now. Mostly it will look the same, because the Scriptures will remain and the Tradition can never be unwound, even if the tree does require occasional pruning. We will still believe in the Trinity and Incarnation; we will still have seven sacraments;[3] we will still have a pope, etc. But theological study will eventually produce new doctrinal conceptualisations and formulas. The Church will experience many things. There will be new popes and new councils, even ecumenical ones. This fact should neither horrify nor titillate us, for it is the law of nature, as the Church journeys to God’s kingdom. As St. Newman beautifully put it in the aforementioned essay: “In a higher world it is otherwise, but here below to live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often” (1,1,7).

1] For example, I recommend Bishop Mark Seitz’s Pastoral Letter on Immigration, as well as Bishop Robert McElroy’s incisive 2013 America piece on structural sin and intrinsic evil, which is once again timely as another election draws near.

[2] There are no shortage of such nostalgic cut-offs. Many Protestants consider the early Church to be legitimate, prior to the “decadence” of the Middle Ages, around the year 600. Some take a more radical view and only consider the first 300 years, before the conversion of Constantine. Some get more radical still and accept only about the first 200 years and the so-called “apostolic fathers.” Similarly, Catholic traditionalists imagine everything was fine before 1958 when John XXIII became pope. The post-Vatican I schism of 1870 was the same way: they called themselves “Old Catholics” because they rejected the “novel” doctrine of papal infallibility.

[3] Could an eighth perhaps be recognised eventually? Probably not, but I would not rule it out completely.

Dr Adam Rasmussen is a Professorial Lecturer in the Department of Theology at Georgetown University. He has a Ph.D. in Theology and Religious Studies from The Catholic University of America, specialising in historical theology and early Christianity. His research focuses on St. Basil, Origen, and the interface between theology and science in their writings. His current research focuses on Basil and the human body, physiology, and medicine. He blogs at https://chrysologus.blogspot.com/

With thanks to Where Peter Is, where this article originally appeared.