“The most dangerous weapon of white supremacy has always been its ability to erase the history of its violence and its victims.” – Dr. Shannen Dee Williams.

It is not uncommon for us to hear astonishment, especially from white people, when they first hear that the Jesuits held people in slavery. Nor is it uncommon to hear assumptions like, “people enslaved to the Jesuits had it better than other enslaved people,” or a dismissal of the topic accompanied by a gross underestimation of the depth to which the Jesuits were involved in the institution of slavery.

The distance that many white Catholics have from the realities of slavery and its persistent legacy is not happenstance; it is due to the erasure or warping of historical memory. This warped memory allows mutations of racism to persist. For example, the same white supremacist logic that allowed Jesuits to justify enslaving black men and women in the nineteenth century enabled them to justify denying Black men entrance into their order into the middle of the twentieth century. This logic also laid the groundwork for present day racism in Jesuit spaces.

In a talk during a conference of the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities, Fr. Bryan Massingale illustrated the racial ideology that undergirded the Jesuits’ decision to carry out the infamous sale of more than 272 women, children, and men by Georgetown University. He said:

“The truth would go somewhere like this: We could not see these black bodies as part of Christ’s body because we saw God as white…We Jesuits could not have seen these 272 black men, women and children as belonging to quite the same faith or Church or God as us. Because the logic of white supremacy dictates that public spaces, rituals, churches and even God belong to white people in a way that they don’t belong to other groups…that religion and holiness and faith belong to white people in a way it cannot belong to others.”

To understand the presence of racism in the Church today, it is necessary to look to our history. As Nikole Hannah-Jones writes, “when it comes to truly explaining racial injustice in this country, the table should never be set quickly: There is too much to know, and yet we aggressively choose not to know it.”

The same can be said of the Church.

Jesuits—and most Catholic religious—treated Black people as objects of ministry rather than as agents in their own faith.

They were able to justify holding people of African descent in bondage because they were more concerned with enslaved people’s salvation than their temporal wellbeing. While Jesuits rationalised their slaveholding by proclaiming they were supplying enslaved people with access to the sacraments and other components of the Catholic faith, they always privileged ministry to white Americans.

They increasingly excluded Black congregants from white spaces of worship by forcing them to stand or sit in the back pews, galleries, or transepts, or to move into a separate chapel altogether. Many deemed their ministry to enslaved and free Black populations—often an afterthought—as a simple task.

They believed enslaved people were so easily led into the faith that they could assign Jesuits in formation to them as a way to practice their training in catechesis and homiletics, while other Jesuits took on religious education to Black Americans as a “hobby.”

Jesuits crafted myths to rationalise enslavement that pervade white conceptions of Catholic slaveholding to this day. The notion of the “priest’s slave” hid the violence of the Jesuits’ slaveholding through the argument that clergy treated enslaved people so indulgently that they could not be controlled, did very little labour, travelled where they wished, and lived almost as if free.

In reality, Jesuits assaulted, manipulated, and overworked enslaved people just like any other slaveholders. People enslaved to the Jesuits regularly protested having their families sold apart; living in crowded, lice-ridden, poorly insulated housing; and having promises denied. Though Felix Verreydt, S.J., believed that “it was a happiness for these coloured people to have all the means necessary to work out their salvation,” he once remarked tellingly:

“We heard sometimes their earnest desire to be free in a free country, it was difficult–not to say almost impossible–to convince them of their happiness.”

While the Jesuits justified exploiting the labour they coerced from enslaved Africans by arguing that they were ‘bringing enslaved people up’ in the faith, they used this stolen labour to support the institutions where they sought to foster the spiritual development of white boys through education.

Most Jesuit schools in the U.S. were what Xavier University in Cincinnati proclaimed to be in its Act of Incorporation: “an institution for the education of white youth.” But Xavier University was, in fact, one of the rare exceptions. There, Jesuits covertly educated mixed-race boys (likely able to pass for white) who were the sons of Louisiana planters and enslaved women, despite prohibitions of regional Black Codes. Their choice to do so, however, was motivated more by the prospect of tuition dollars, the support from wealthy Catholic parents, and the opportunity to offer pathways toward salvation, than any principles of equality.

When Xavier had to close its doors to boarding students in 1854 due to financial troubles, Jesuits encouraged white students to go to Saint Louis University and to Saint Joseph College in Bardstown, Kentucky (now closed), but knew that the students of African descent would be denied admittance. In fact, three students at Bardstown had recently been dismissed for “having been proven to be of mixed blood.”

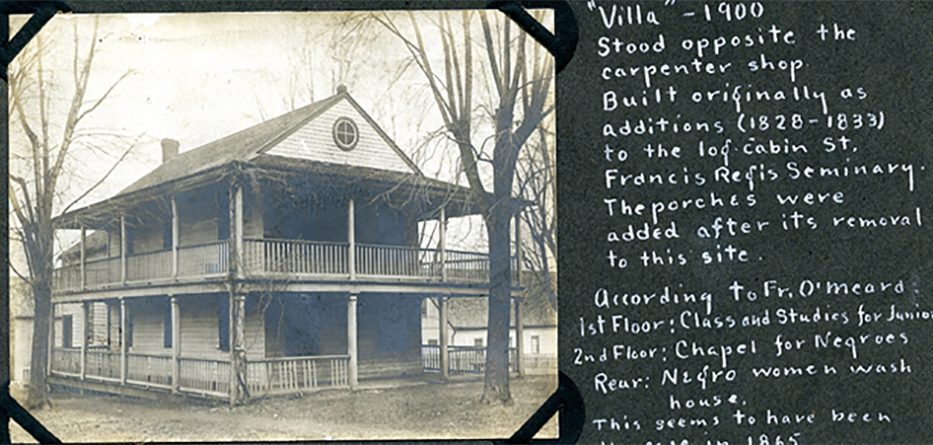

Ruins of the first Saint Francis Xavier College Church in St. Louis, c. 1870s. The gallery in the upper right of the church is labelled in this picture as “1st Jesuit Negro Chapel, Old St. F. X. Church.” Image used with permission from the Jesuit Archives and Research Center, St. Louis, Missouri, and Daily Theology.

Fear of public sentiment and desire for public support motivated the Jesuits’ exclusionary practices as they absorbed white supremacist beliefs.

“Bardstown and Saint Louis could not receive them without offense. Moreover, all the white pupils would leave at once,” wrote Vice-Provincial William Stack Murphy. The Jesuits feared not only divestment from their institutions, but also violent repercussions, as in St. Louis, where mobs of white men forced the closure of a school for enslaved and free Black girls run by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, which was shortly followed by state-wide laws forbidding the education of Black residents.

American Jesuits never had a formal policy excluding Black men from entering the order but the practice of such exclusion was strong.

After slavery’s abolition, Jesuits continued to practice racial exclusion by denying Black men admittance to the order, as was the experience of Hermann Koch, who entered the novitiate in Grand Coteau, Louisiana, in 1875 only to find that his fellow scholars refused to dine with him. Jesuits dismissed him after he was determined to have features “peculiar to the Negro race.” The following two images, from Jesuit records from Grand Coteau, tell the story:

Image used with permission from the Jesuit Archives and Research Center, St. Louis, Missouri and Daily Theology.

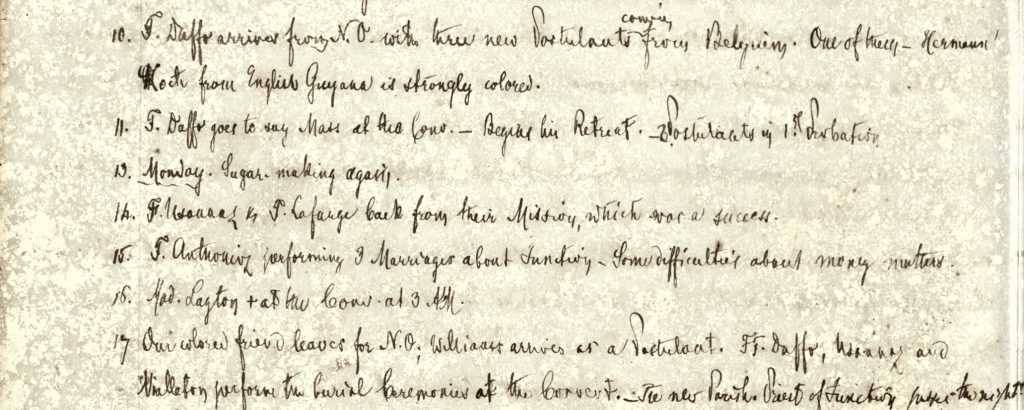

The Jesuit Minister’s Diary of Grand Coteau in 1875 announces that when three new postulants arrived at the novitiate from Belgium, “One of them, Hermann Koch from English Guyana is strongly coloured” (top of image). Seven days later, he was dismissed, the diary entry reading “Our coloured friend leaves for N.O.” (bottom of image).

Image used with permission from the Jesuit Archives and Research Center, St. Louis, Missouri and Daily Theology.

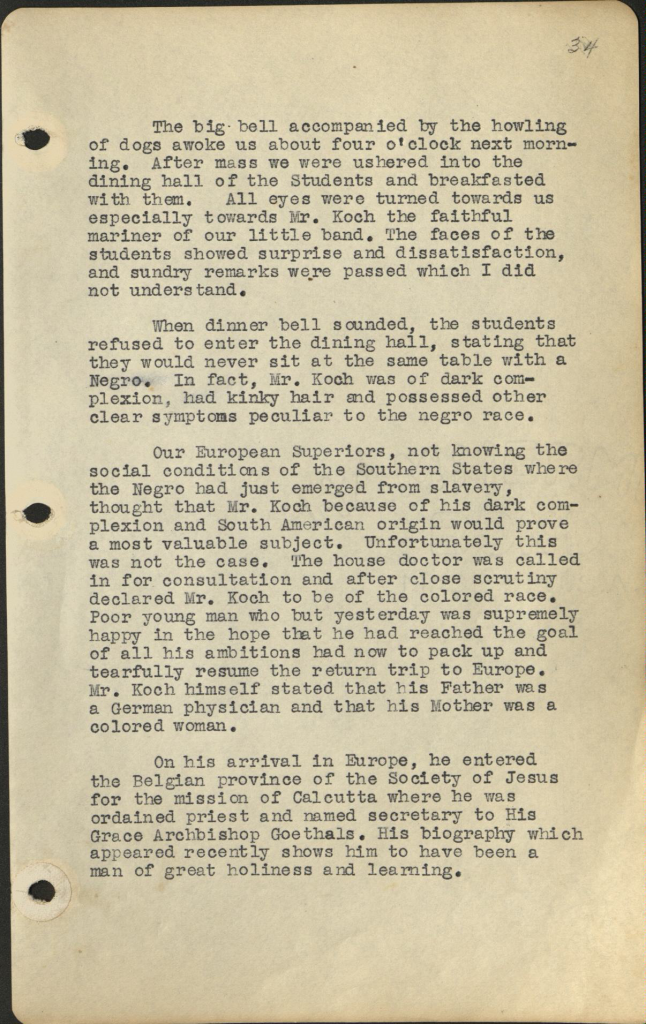

The above excerpt is from the memoirs of Albert Biever, S.J., who had entered the Jesuit novitiate with Hermann Koch in 1875. Biever recounts how “all eyes were turned…with dissatisfaction” when Hermann Koch and the other novices entered the room. He then describes how Koch was dismissed by the American Jesuits because he had “dark complexion, had kinky hair and possessed other clear symptoms peculiar to the negro race.”

Jesuits also stripped agency from Black Catholics who pushed for their own spaces to worship free from discrimination, taking the credit for founding these Black Catholic churches themselves. Even Jesuits like William Markoe and John LaFarge who worked toward integration usurped leadership from Black activists.

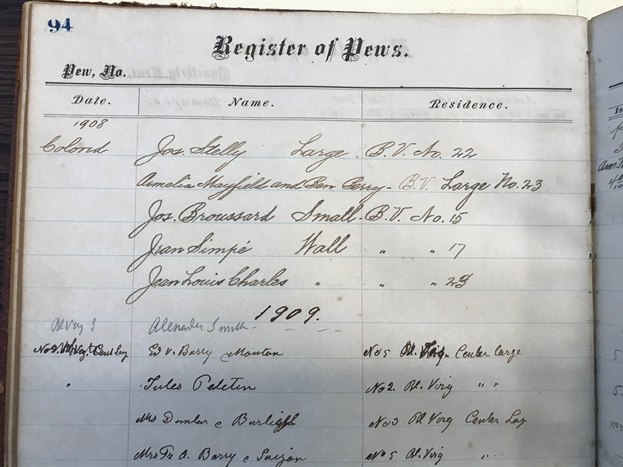

Pew rent books show segregated worship within the Jesuit-run St. Charles Borromeo Church in Grand Coteau, Louisiana in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Image used with permission from the Jesuit Archives and Research Center, St. Louis, Missouri and Daily Theology.

This practice of exclusion, along with the rhetoric surrounding the decision to end such practices, reveals that white Jesuits understood religious life to belong to white people in a way it didn’t belong to people of colour.

In 1945, Fr. Zacheus Maher, the North American Assistant to Fr. General in Rome, wrote that American provincials had asked him several times “to declare what should be regarded as the position of the Society [of Jesus] in America towards the admission of otherwise properly qualified negro applicants.”

Maher emphasised the importance of “usefulness” as a main criterion for considering an applicant to the order, in accordance with the Jesuit Constitutions. He wrote that “such a candidate ought not to be excluded merely because of his colour. If, however, because of his colour it is judged that he will not be useful in a given province, then efforts should be made to find a Province in which he will be useful, and he should be accepted for that Province.”

The category of “usefulness” was easy code for white.

In 1944, John LaFarge had written to Maher to explain this. LaFarge told Maher of a “well-qualified” candidate to the Jesuits with a good record in studies and conduct at the Jesuit college in Jersey City who was denied admission into the Jesuits because he was Black. During a meeting with the provincial the candidate was told, “there would be no place to use him in the New York Province.”

“Usefulness” did not carry the same meaning for a Black man and a white man. The main factor that disqualified Black candidates from being “useful” was the white Jesuit assumption that a Black man could not stand in a position of authority over whites. Because of this, the Provincial would be unable to send a Black man to teach in white high schools or parishes. For Black candidates, the ability to minister was defined by white comfort over, say, a calling from God or the rite of ordination.

This was evidenced clearly in a 1952 meeting of the New Orleans Province on the topic of race relations. While discussing the acceptance of Black applicants, one of the worries listed was “racial prejudice among our novices, more particularly among their parents,” as well as the difficulty in placing Black Jesuits in teaching positions in white populated high schools.

Nevertheless, the New Orleans Jesuits decided to begin accepting Black men into the novitiate. A full proposal of their new practices regarding “race relations,” including the decision to admit ‘qualified’ Black men who gave promise of “assimilation,” was sent to Fr. Jean-Baptiste Janssens, the Superior General in Rome. Janssens wrote back with his own charges of white supremacy.

“I ask that we whites not believe that we have the criteria of a better education among all men. I have long found more exquisite urbanity, if I might give only one example, among African adolescents in the Congo than among us Europeans. I ask that it not be required that they be assimilated to us but rather that we might imitate them in this manner!”

Cultural racism has not vanished from the Jesuits. In a 2005 essay in the journal Studies in the Spirituality of the Jesuits, Fr. Greg Chisholm, S.J. wrote about the challenges and joys of being a Black Jesuit in an order largely shaped by white European culture. He wrote of the need to adopt a new consciousness in order to survive.

“In this consciousness, I am aware of how to act, how to enjoy the humour, how to envision the world, how to draw from the cultural wellspring in the way Irish-Americans do….My own cultural consciousness was there as well, sometimes rebelling against the unfairness, sometimes mocking the other, sometimes offering protection and consolation, most times bemoaning my capitulation, and always being the place from which I communicated with God.”

Of his fellow Black Jesuits, he wrote: “Almost all have known the tensions of being Black and Jesuit in the United States. Almost all have had to discern choices that would offer a measure of peace for their hearts and minds.”

To this day, people of colour continue to report experiencing racism in Jesuit institutions.

These dynamics are not exclusively a Jesuit problem, as they are indicative of a broader reality in American society. They are a Jesuit problem, however, because, from their beginnings in America, many Jesuit institutions and the order itself, privileged white people at the exclusion of Black people—the inertia of that culture has not been adequately interrupted.

This was supported by thinking that religion or education belonged to white people in a way they didn’t belong to people of colour. While they believed Black Americans could receive their ministry, Jesuits did not consider them capable or worthy of exercising ministry themselves. Without a significant recognition of how this ideology has contributed to present-day racism, we cannot expect it to vanish.

Kelly L. Schmidt is a historian of slavery & race, abolition, and African American history. She is a PhD Candidate in United States History and Public History at Loyola University Chicago, and serves as Research Coordinator for the Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation Project, an initiative of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States.

Billy Critchley-Menor, S.J., is a graduate student in American studies at St. Louis University. He is on the leadership team of the Jesuit Antiracism Sodality and works with the Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation Project of the Jesuit Conference. He is a member of the Midwest Province of the Society of Jesus.

This post is part of Daily Theology’s Symposium on Racism, White Supremacy, & the Church. Click here for more information.

Reproduced with permission from Daily Theology.